“GraphQL is a front-end technology”, “Federation is the only solution for unified graph and, services orchestration”, “GraphQL is a replacement of REST” are common misconceptions that are most likely linked to biased learning of GraphQL.

Because of its rapid ecosystem evolution in the past years, learning GraphQL in 2022 is more challenging than it used to be.

For this reason, this article, greatly inspired by “How not to learn TypeScript” and “How not to learn Rust”, will guide you to avoid common learning biases and misconceptions around GraphQL.

Mistake #1: GraphQL Is a Front-End Technology

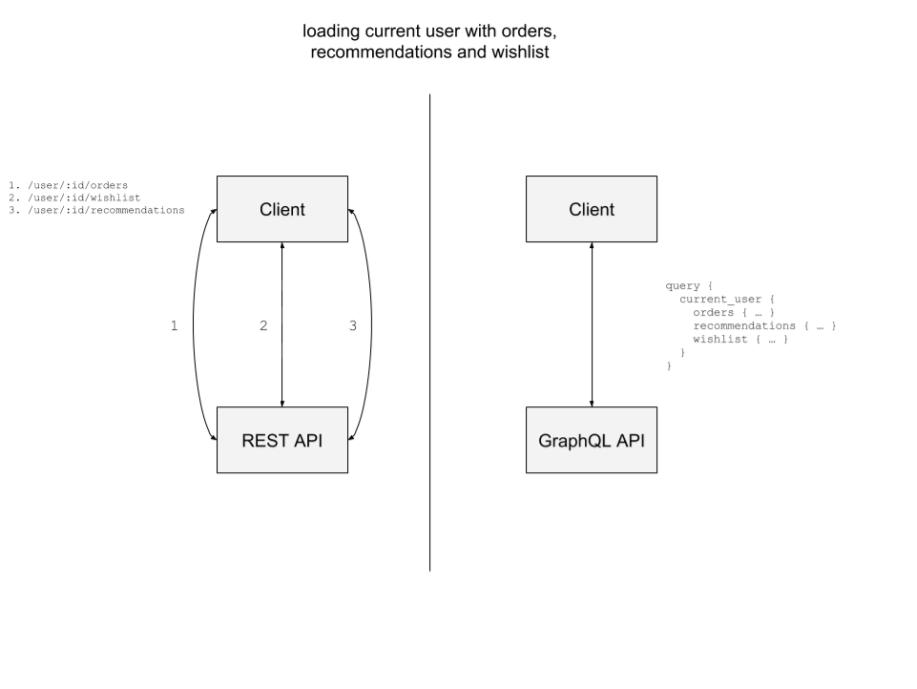

Yes, is it true that GraphQL was first popularized as a technology solving issues on the client-side (mobile/web apps) by:

- reducing the number of roundtrips with the API(s)

- reducing the size of fetched data by requesting only the necessary fields

- removing the overhead of fetching and crunching data from multiple endpoints

In short, GraphQL gave the control back to the data consumers (mobile apps, web apps).

GraphQL as an Innovative Solution to Microservices Orchestration

However, starting in 2018, the GraphQL ecosystem started to grow, especially on the back-end side, where new horizons of GraphQL were developed.

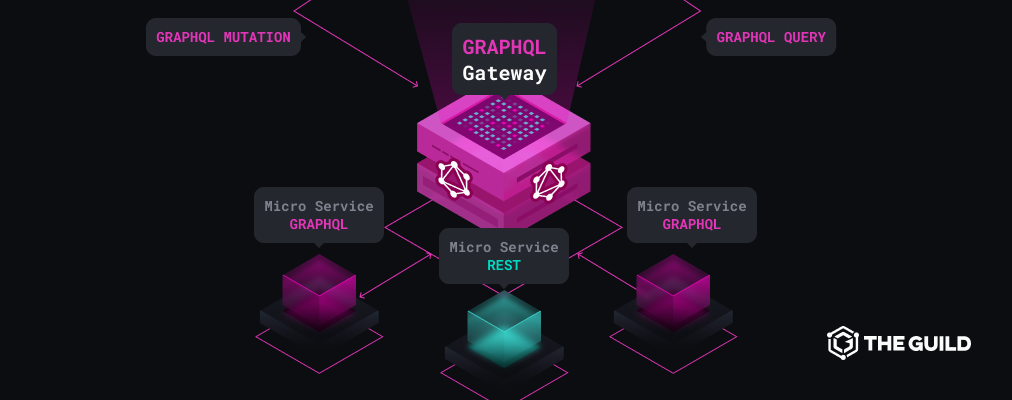

Many open-source actors started to propose solutions for unified schema/services orchestration, to name the major ones: GraphQL Tools, Apollo Federation, Hasura, GraphQL Mesh.

Rapidly, some companies started to offer enterprise solutions such as SaaS/PaaS to manage GraphQL schema at scale: Apollo Studio, AWS AppSync, Hasura Cloud.

GraphQL’s Path on Back-End Use-Cases

Not limited to services orchestration, GraphQL continued its goal to become the go-to language for data.

Recent projects such as GraphQL Mesh or products such as Hasura Cloud proved that GraphQL has a purpose beyond the simple front-end/mobile apps fetching challenges.

Other actors, such as Neo4J, a historical graph database actor, announced support for GraphQL as a data query language.

Mistake #2: Design GraphQL APIs like REST APIs

When designing a GraphQL Schema, many projects decide to keep a 1-1 relationship with the underlying data schema (database or other microservices).

Marc-André Giroux covered this subject in the “GraphQL Mutation Design: Anemic Mutations”. The term Anemic refers to a design where a Mutation (or Query) only contains data, not behaviors.

A good GraphQL Schema design should:

- simplify the usage by providing the proper abstractions (ex: aggregated fields, atomic mutation across multiple microservices)

- provide specialized mutations that represent specific behaviors instead of CRUD mutations directly linked to an underlying data-schema

For example, for a schema exposing a query to update a User type as follows:

type User {

id: ID!

name: String!

email: String!

firstName: String

lastName: String

plan: UserPlan!

premiumPreferences: UserPremiumPreferences

}

enum UserPlan {

DEFAULT

PREMIUM

}

type UserPremiumPreferences {

alerts: Boolean

alertsFrequency: Boolean

# ...

}A “data-driven” GraphQL Mutation for updateUser would be the following:

input UpdateUserPremiumPreferences {

alerts: Boolean!

alertsFrequency: String

}

input UpdateUser {

name: String

email: String

firstName: String

lastName: String

premiumPreferences: UserPremiumPreferences

}

type Mutation {

updateUser(id: ID!, input: UpdateUser!): User

}As explained in Marc-André Giroux’s article, the above mutations expose a lot of optional fields, making the typing of the mutation obsolete (and also the self-documentation).

By removing any nullability constraints on the input fields, we’ve pretty much deferred all this validation to the runtime, instead of using the schema to guide the API user towards proper usage.

GraphQL Mutation Design: Anemic Mutations.

A better, behavior-driven, design would be the following:

input UpdateUserPremiumPreferences {

alerts: Boolean!

alertsFrequency: String

}

input UpdateUser {

name: String

email: String

firstName: String

lastName: String

}

type Mutation {

updateUser(id: ID!, input: UpdateUser!): User

updateUserPreferences(id: ID!, input: UpdateUserPremiumPreferences!): User

}We now offer specialized mutations where the end-user developer won’t have to guess which fields are required and will get better static validations of the mutations arguments.

Remember that a GraphQL Schema is neither a back-end nor front-end owned technology; it is a technical part of the stack that both parts must shape.

Whether you build a product API or gateway of microservices, the goal of a GraphQL API is to provide a simplified abstraction of a set of business logic.

Mistake #3: Learning GraphQL Only through Apollo

The Apollo company has been one of the leading early contributors of GraphQL and still is a prominent actor of the ecosystem.

However, while most Apollo projects still keep a good share of usage and overall SEO presence, it is worth mentioning that new equivalent projects and alternatives rose in the past years.

Browser GraphQL Clients

Regarding web-based client GraphQL Client, apollo-client is no longer the only viable solution.

urql came as a solid and different vision of a GraphQL client design, not just as an alternative, with:

- Flexible cache system

- Extensible design (easing adding new capabilities on top of it)

- Lightweight bundle (~5x lighter than Apollo Client)

- Support for file uploads and offline mode

In the React ecosystem, React Query (especially when used with GraphQL Code Generator) brings a lightweight and agnostic solution for GraphQL.

React Query is a great candidate if you are looking for an easy-to-use and lightweight multipurpose client (GraphQL-capable) that provides essential features such as:

- Powerful cache (background refresh, window-focus refreshing)

- Advanced querying pattern (parallel queries, dependent queries, prefetching)

- UX patterns: optimistic updates, scroll restoration

- Great dev tools

Finally, when it comes to building simple applications that might not need caching or optimistic UIs

capabilities, the famous graphql-request library

is a perfect companion!

This lightweight library comes with the essential features to query a GraphQL API:

- Mutations validation

- Support for File upload

- Batching

- Promise-based API

- TypeScript support

Server GraphQL Libraries

The same trend applies on the server-side, where many libraries are now widely used.

Due to its historical presence and leading solutions for Apollo-powered technologies such as Federation, Apollo server still has a significant usage share.

However, many new companies and projects prefer more opinionated or lightweight alternatives.

Nest.js is an excellent alternative for GraphQL APIs building for Angular design and DDD lovers. Nest.js comes with:

- Fully-typed resolvers building experience

- Strong structuring patterns such as repositories, services, etc

- Logging system

- Support for Apollo Federation

Nest.js is a great choice if you look into an opinionated and structured way to build your GraphQL APIs.

On the other hand, other non-opinionated libraries such as GraphQL Yoga focus on bringing the best developer experience in building extensible GraphQL servers.

GraphQL Yoga comes with a performant HTTP server that provides:

- subscriptions over HTTP (SEE)

- support for

@deferand@stream - out of the box uploads and CORS capabilities

- Extensible design with the Envelop plugins system

- Apollo Federation support

- Easy integration with Next.js, Svelte Kit, Cloudflare workers, and more!

A New Learning Path

As we can see, GraphQL offers multiple solutions from front-end, back-end, databases to SaaS.

If you start learning GraphQL, an excellent place to start is howtographql.com, where you’ll be able to test multiple frameworks and find the ones that best fit your stack and product/project.

Mistake #4: Throwing Errors from Resolvers

For most new adopters (especially coming from REST APIs), having GraphQL APIs returning 200 OK on

errors seems like a flaw.

However, while this design choice is entirely legit (GraphQL is bringing back the real purpose of HTTP status code that REST hijacked), another aspect of error handling in GraphQL is not.

Most GraphQL resolvers implementation handle errors as follows:

const resolvers = {

Query: {

user(parent, args, context) {

// ...

throw new Error('User not found')

}

}

}Doing so returns the following response:

{

"errors": [

{

"message": "User not found",

"locations": [{ "line": 6, "column": 7 }],

"path": ["user", 1]

}

]

}As explained by Laurin from The Guild in this article, using this error pattern is a bad habit since:

- Errors need to be parsed on the client-side (we “guess” the error by parsing the error message)

- Errors are not colocated while Queries are designed to shape data on the UI

Elegant GraphQL Errors with Union Types

A more elegant way to emit error in GraphQL is to use Union types for expressing expected errors as follows:

type User {

id: ID!

login: String!

}

type UserNotFoundError {

message: String!

}

union UserResult = User | UserNotFoundError

type Query {

user(id: ID!): UserResult!

}Allowing us to write the following query:

query {

user(id: 1) {

... on User {

id

login

}

... on UserNotFoundError {

message

}

}

}Now, the fetched response reflects the correct errors in a type-safe and colocated way:

{

"data": {

"user": {

"message": "User not found",

"__typename": "UserNotFoundError"

}

}

}More details are available in the Handling GraphQL errors like a champ with unions and interfaces article.

Note: Error masking is also an excellent approach that does not require updating the schema: https://graphql-yoga.com/docs/features/error-masking.

Mistake #5: “Federation Is the Only Viable Way to Compose Schemas”

Federation Is Opinionated Stitching

Apollo’s Federation is commonly brought as the solution to compose schemas or build a microservices’ architecture with GraphQL.

While Federation has been brought under a new name as a distinct solution to Stitching, the reality is actually quite different.

Stitching is a design that consists of a single GraphQL gateway schema that composes multiple underlying GraphQL services.

It can be achieved with 3 approaches: Federation, Modern Stitching and, Schema Extensions.

Taking the following subschemas:

# Posts subschema

type Post {

id: ID!

text: String

userId: ID!

}

type Query {

postById(id: ID!): Post

}

# Users subschema

type User {

id: ID!

email: String

}

type Query {

userById(id: ID!): User

}Let’s see 3 distinct Stitching approaches to add the User.posts sub-query:

Federation

Federation architecture is actually stitching. It stitches subschemas (via an Apollo Gateway) by

providing a set of Type Merging directives (@requires, @key, @external).

Each “entity type” must originate by a single service and can be extended by using a mix of schema

extensions (extend type) and the Federation’s SDL directives.

To add the User.posts sub-query, the following schemas would be required:

# Posts subschema

type Post {

id: ID!

text: String

userId: ID!

}

extend type User @key(fields: "id") {

id: ID! @external

posts: [Post!] @requires("id")

}

extend type Query {

postById(id: ID!): Post

}

# Users subschema

type User @key(fields: "id") {

id: ID!

email: String

}

extend type Query {

userById(id: ID!): User

}Modern Stitching

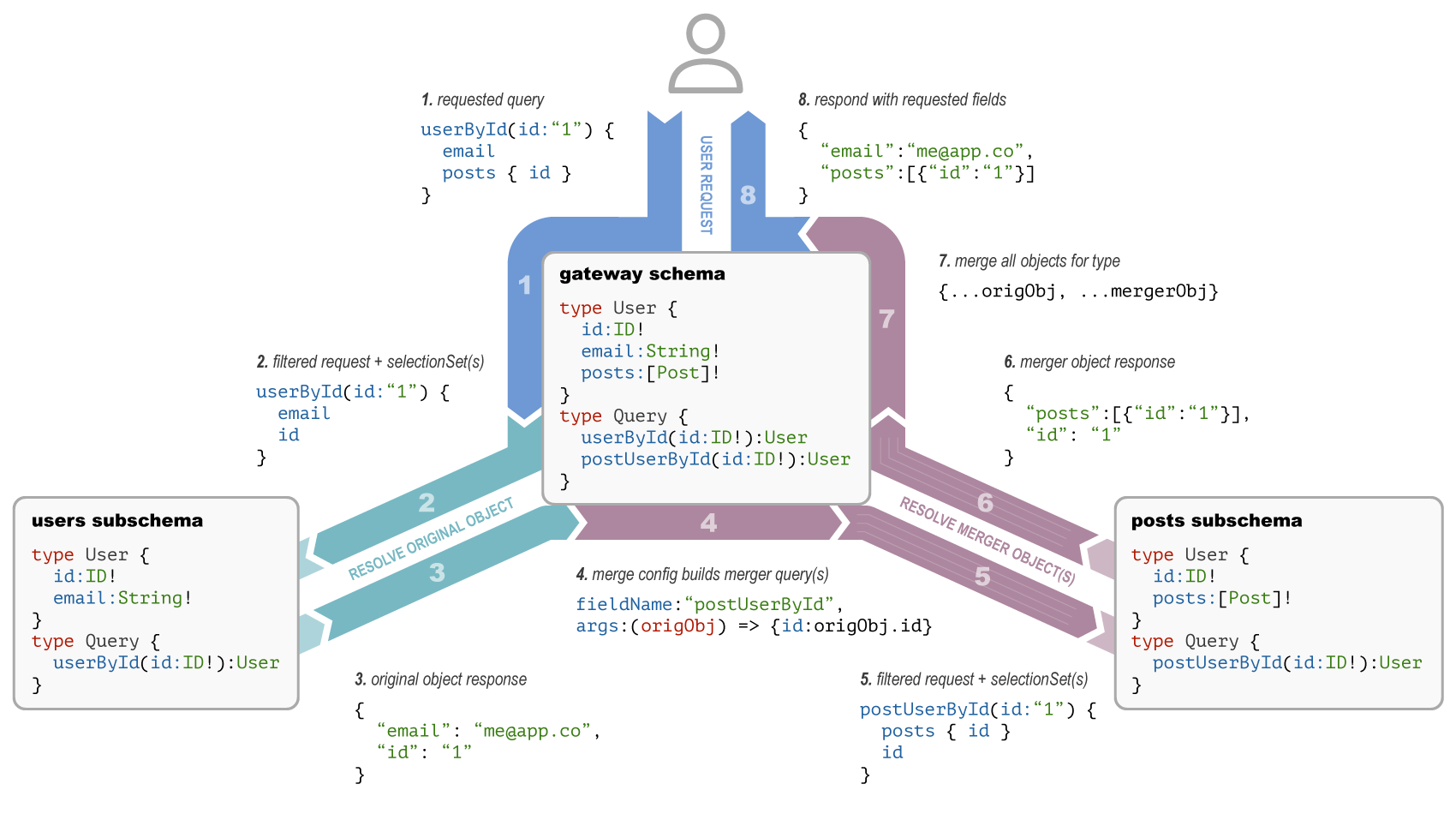

Modern Stitching (GraphQL Tools v7+) is relying on a programmatic approach where each subschema is totally independent.

Only the gateway must provide type merging information to indicate who must resolve fields shared across multiple services.

After simply adding the posts: [Post!]! field to User, in the “posts” subschema:

# Posts subschema

type Post {

id: ID!

text: String

userId: ID!

}

type User {

id: ID!

posts: [Post!]!

}

type Query {

postById(id: ID!): Post

postsByUserId(userId: ID!): User

}

# Users subschema

type User {

id: ID!

email: String

}

type Query {

userById(id: ID!): User

}and adding the following gateway configuration will be required:

import { stitchSchemas } from '@graphql-tools/stitch'

const gatewaySchema = stitchSchemas({

subschemas: [

{

schema: postsSchema,

merge: {

User: {

fieldName: 'postUserById',

selectionSet: '{ id }',

args: originalObject => ({ id: originalObject.id })

}

}

},

{

schema: usersSchema,

merge: {

User: {

fieldName: 'userById',

selectionSet: '{ id }',

args: originalObject => ({ id: originalObject.id })

}

}

}

]

})The final stitched schema could also be built similarly to Federation by using type merging

directives (@merge, @canonical):

# Posts subschema

type Post {

id: ID!

text: String

userId: ID!

}

type User {

id: ID!

posts: [Post!]!

}

type Query {

postById(id: ID!): Post

postsByUserId(userId: ID!): User @merge(keyField: "id")

}

# Users subschema

type User {

id: ID!

email: String

}

type Query {

userById(id: ID!): User @merge(keyField: "id")

}Schema Extensions

Schema extensions, similar to the initial Stitching proposals, is a different approach where individual subschemas are only exposing their own types.

The gateway becomes responsible for merging and enriching the final schema by using Schema Extensions:

// ...

export const schema = stitchSchemas({

subschemas: [postsSubschema, usersSubschema],

typeDefs: /* GraphQL */ `

extend type Post {

user: User!

}

extend type User {

posts: [Post!]!

}

`,

resolvers: {

User: {

posts: {

selectionSet: `{ id }`,

resolve(user, args, context, info) {

return delegateToSchema({

schema: postsSubschema,

operation: 'query',

fieldName: 'postsByUserId',

args: { userId: user.id },

context,

info

})

}

}

},

Post: {

user: {

selectionSet: `{ userId }`,

resolve(post, args, context, info) {

return delegateToSchema({

schema: usersSubschema,

operation: 'query',

fieldName: 'userById',

args: { id: post.userId },

context,

info

})

}

}

}

}

})Modern Stitching Architecture

Schema Stitching (a component of GraphQL Tools[v6 and under]) got a bad rap when it was famously abandoned by Apollo in favor of their Federation architecture some years back. However, Stitching came under the stewardship of The Guild and friends in 2020, and they’ve since overhauled it with numerous automation and performance enhancements. Seemingly out of nowhere, Schema Stitching has reemerged as something of a nimble hummingbird racing alongside the stallion that is Apollo Federation.

https://product.voxmedia.com/2020/11/2/21494865/to-federate-or-stitch-a-graphql-gateway-revisited

While initial Schema Stitching implementation (similar to Schema Extensions) had verbose configuration and performance issues (lack of batching), the Modern Stitching (GraphQL Tools v7+) relies on Type Merging that provides great performance and developer experience.

Let’s review the main features of Modern Stitching and how it differentiates from Federation.

Explicit Fields Resolutions via Queries

Modern Stitching does not require types to have an origin (like Federation entities).

All subschemas, being independent, can define types that might exist in other sibling services.

The only requirement to allow GraphQL Tools to merge types together is that each subschema must expose a query to resolve a type, as follows:

# Posts subschema

type Post {

id: ID!

text: String

userId: ID!

}

type User {

id: ID!

posts: [Post!]!

}

type Query {

postById(id: ID!): Post

postsByUserId(userId: ID!): User

}

# Users subschema

type User {

id: ID!

email: String

}

type Query {

userById(id: ID!): User

}Here, our “Posts” subschema adds a field to the User type (User.posts).

To be able to resolve the User type on the following query:

query UserPosts {

userById(id: "1") {

email

posts {

id

}

}

}We need to add the postsByUserId(userId: ID!) query to resolve the User type on the “Posts”

service.

As explained in the

GraphQL Tools v7+ documentation,

here is the merging flow performed when processing the UserPosts operation:

Modern Stitching’s Type Merging approach follows the initial design of GraphQL resolvers but for types sharing fields across multiple subschemas.

Such design leaves your subschemas independent (working on a schema only requires local knowledge) and built using vanilla-GraphQL (without a framework-specific mental model) while the stitching configuration is done at the gateway level.

Improved Performance with Automatic Batching

The main reproach made to the old Stitching approach was around performance.

Modern Stitching brings fast Type Merging with 2 features:

Batching

Let’s say that we execute the following operation on a new users query added to the Users service:

query UsersPosts {

users {

email

posts {

id

}

}

}In order to resolve each user’s posts, Modern Stitching will have to call postsByUserId Query on

the Posts service many times.

Fortunately, if we transform the existing postsByUserId by the following:

postUsersByIds(ids: [ID!]!): [User]!and properly configure our gateway, Modern Stitching will group the User.posts resolutions into a

single postUsersByIds query to the Posts service.

Query batching

The same logic is applied by Modern Stitching at a higher level.

If an operation needs to call a service multiple times, all those operations will be merged as one. For example, on a hypothetical Products schema, the following queries:

query {

products(ids: [1, 2, 5]) {

name

}

}

query {

seller(id: 7) {

name

}

}

query {

seller(id: 8) {

name

}

}

query {

buyer(id: 9) {

name

}

}Will be transformed to the following unique operation that will be sent to the Products service:

query {

products_0: products(ids: [1, 2, 5]) {

name

}

seller_0: seller(id: 7) {

name

}

seller_1: seller(id: 8) {

name

}

buyer_0: buyer(id: 9) {

name

}

}Those two features (Batching and Query batching) significantly improve the performance of a Modern Stitching architecture at scale.

The Flexibility of Server Implementations: No Subscriptions Limitation

When used with the Modern Stitching programmatic API (without the @merge and @canonical

directives), building subschemas is achieved with vanilla GraphQL.

It means that each subschema can be built with any technologies, framework, and libraries and require no compatibility work (while Federation requires subschemas to use a Federation-compatible GraphQL server).

It is also true for the gateway server.

Modern Stitching is a set of utilities that let you choose your own GraphQL-compatible HTTP server/library (JavaScript):

- GraphQL Yoga

- Nest.js

- GraphQL Helix + Express

- Apollo Server

Finally, Modern Stitching allows you to support GraphQL Subscriptions in a composed schema (over WS or SEE).

You Might Not Need Stitching

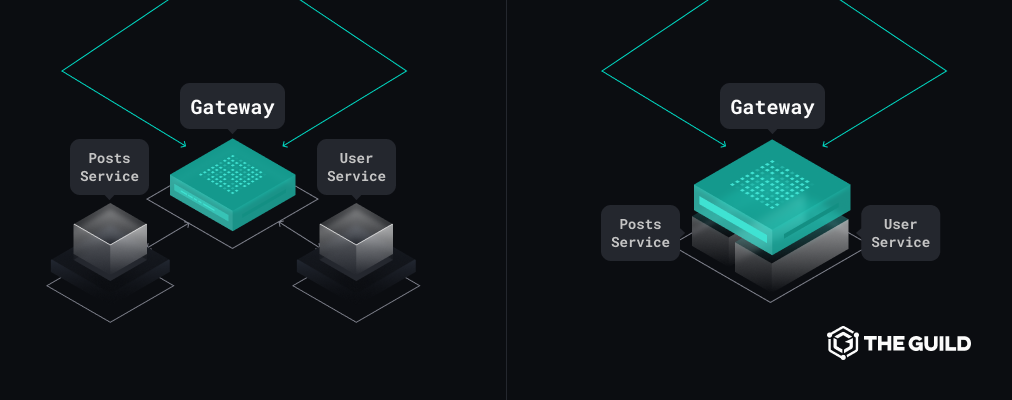

Today, the most popular solutions for composing a unified GraphQL layer are done over the network (stitching with remote schemas or via Apollo Federation gateway).

The main reason for doing that is the separation in development and deployment workflows and allowing teams to have ownership over the schema.

However, such a setup creates performance issues due to the network overhead.

While Apollo works on a software solution to gap the gateway latency, a solution might reside at the organization level.

Another popular trend in the JavaScript ecosystem is monorepo.

Thanks to the evolutions of tools (lerna, yarn workspaces) and from the GitHub platform (code owners system), monorepo is a viable and frequent pattern for teams to work together on a complex stack.

The separation in development and deployment workflows and allowing teams to have ownership over the schema can also be achieved by merging the subschemas at build time and deploying it as a gateway that runs local modules, with no network overhead.

Using a monorepo with schema merging at build time solves the incompressible performance issue while preserving the ownership of the subschemas and guaranteeing that deployed subschemas are compatible.